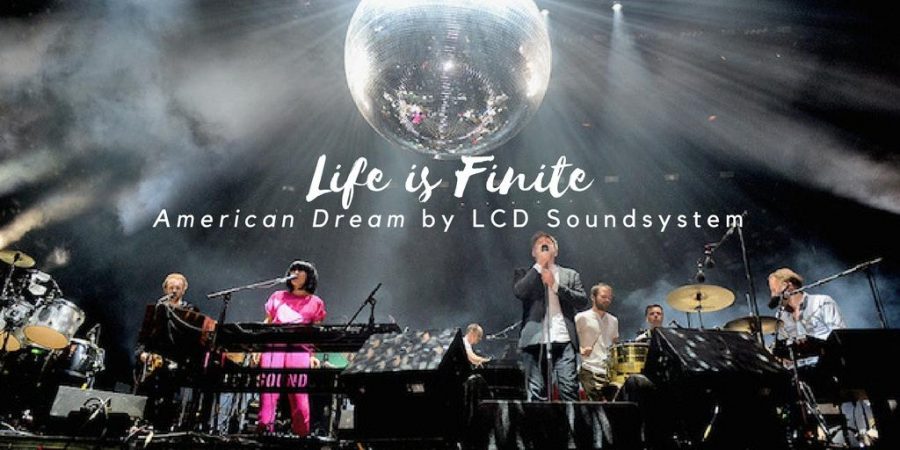

Many reviews of the new LCD Soundsystem album, American Dream, start by analyzing and/or rehashing James Murphy’s decision six years ago to break up the band at the height of their indie dance rock glory and his decision last year to bring the group back. He had his reasons, both for the breakup and the comeback, and you can read all about it in hundreds of other places if that’s what interests you about LCD Soundsystem’s new album. I’m not going to get into it. So I’ll start here: LCD Soundsystem made three great studio albums prior to their breakup, and two of these albums, 2007’s Sound of Silver and 2010’s This is Happening, are full-fledged masterpieces. With the new album, American Dream, the first new LCD Soundsystem studio album since 2010, Murphy also achieves masterpiece status. American Dream does what great art should do: it stirs, evokes, challenges.

Much of LCD’s catalog contains poignant (but danceable) reflections on getting older and meditations on our individual place in the world, and these themes reappear in full force on American Dream, but this time these ideas take on a seemingly more serious and foreboding weight. Though this is not a political album (except in a few spots), it is hard to listen to sounds and words that reflect so much existential dread and not feel the long, dark shadow cast by today’s polarized and ever-more-dark world pulsing through as an underbeat of the songs.

That said, the album starts off on what seems to be a positive note in the downtempo “oh baby.” With the familiar “wah wah” bass synth sound made famous in the LCD masterwork “Someone Great,” combined with Murphy’s smoothest-yet vocals (he’s not exactly known as a crooner), “oh baby” feels like some kind of slow, synthesized take on a 50’s doo-wop song. As new layers of keyboards get added on, however, the lyrics quickly reveal that this is not a love song, and instead we are left with a contemplation of longing–a gorgeous one and a beautiful start to the album.

Murphy loves to catalog his musical influences, sometimes in words (see “Losing My Edge” from their debut album) but usually in sound. Much has been made in other reviews that Murphy’s love of late 70s/early 80s-era Talking Heads rears its head on this album, and that is definitely true. On “other voices,” the Talking Heads tribute is hard to deny, but those resemblances aside, “other voices” is quintessential LCD Soundsystem, with its driving bass line, layers of percussion, screeching guitar, sporadically shouted vocals (“OTHER VOICES!”), and crescendoing structure. The highlight of this crescendo is keyboardist Nancy Whang’s brief stint on vocals–“Tell ‘em, Nancy”–which adds a level of rhythmic dystopia to the self-reflective song: “These are the halls that we’re presently haunting / And these are the people we currently haunt.” This song likely reflects Murphy’s anxiety about reforming the band and making new music, and he references his own story about talking with his idol David Bowie about this nervousness. Reportedly Murphy told Bowie that re-forming LCD Soundsystem made him uncomfortable, and Bowie replied, “Good, you should be uncomfortable.” This quotation is now the closing line of this song.

With “i used to,” we get a mid-tempo propulsion of steady drums, early goth guitars, and the most Smiths-like lyrics in the LCD repertoire, including the Morrissey-esque falsetto on the repeated outro: “I’m still trying to wake up.” I know students are too young to know about people dancing to goth music at clubs, but picture a lot of people in all black dancing around like stylized cats, and that’s what this conjures up in my head. That’s praise by the way; this song is awesome.

Murphy brings the self-doubt on “change yr mind,” which is probably about trying to continue being a musician and whether he has anything relevant to say anymore (“And I’m not dangerous now / The way I used to be once / I’m just too old for it now / At least that seems to be true”). Interspersed with quirky electric guitar sqwerks (a word I stole from Radiohead), the song seems to come to a positive resolution that it’s ok to change your mind, like about breaking up your band or things like that.

Electronic tribal beats begin the album’s centerpiece, “how do you sleep?” Almost immediately this beat reminded me of “In a Lonely Place,” which is a fairly obscure, very early New Order b-side. The New Order song is extremely dark, and was actually written as a Joy Division song but recorded as one of the first New Order songs after the death of Joy Division’s lead singer Ian Curtis. This LCD song is–fittingly–about the death of a friendship, though this one by estrangement rather than suicide. Apparently “how do you sleep?” (which shares a title with a scathing anti-Paul song by John Lennon) is about Murphy’s former friend and business partner, but to me the specifics are not important here. Rather, with his almost plaintive wail, Murphy sings bitingly about his own experience in a way that underscores the universality of betrayal (“I remember when we were friends / I remember calling you friend”). Swirling synths complement the dark drum beat, and then . . . about 3:40 into the 9:12 song, that familiar LCD wah-wah bass synth sound appears, but it has never been more ominous. The tribal drums drop off, replaced by a steady beat, with Murphy almost yelling his almost-revenge. The keyboards and drums start to morph into a dance song, reminiscent of a darker version of “Dance Yrself Clean” or “I Can Change” from This is Happening. But the real emotional core of the lyrics comes when Murphy shifts blame from his friend’s betrayal to his own inability to get over it (“Erasing our chances / just by asking “How do you sleep?”). It is a jarring transformation of attitude, and the shifting sounds in this haunting song underscore that tension. “how do you sleep?” jolts me with its increasingly danceable bleakness.

But that darkness gives way (though not entirely) on the next song (and third single) “tonite,” which is a much more classic LCD dance song. Murphy covers familiar territory here, such as his obsession with getting older and trying to remain relevant, as well as his commentary about the state of the music industry today. He returns to his clever, smart-ass persona we’ve seen on so many LCD songs, but he actually does conclude on a high note here, suggesting that the idea that as we get older we fear that we’ve wasted our time on nonsense is just a lie and perhaps we shouldn’t feel such dread. “tonite” is fantastic, and will be a floor-filler at my friends’ parties in the future (especially if I’m DJing).

The first single from American Dream was “call the police,” and having heard LCD play this song live at this summer’s Pitchfork Festival, I can say firsthand that it fits extremely well in the LCD catalog. “call the police” is catchy, complicated, and fun/sad, and provides the first explicit these-are-the-times-we-live-in political feeling on the album, though as I noted, that shadow hangs over much of the album. Like several earlier LCD songs, this one pretty clearly pays homage to David Bowie (one of Murphy’s idols, as mentioned above) in its musical style, especially the drums and guitar. The lyrics cover a wide swath of modern life, including youthful rebellion (both honest and misguided), old white men’s fear of losing power, and even Rousseau’s warnings about social class divide. And all this to a driving beat that will bring the fun to any system-smashing dance party.

Second single “american dream” slows things down again, with its swaying synthesizers and downtempo swagger. But I don’t recommend slow-dancing with your sweetheart to this song. Couched in terms of a terrible one-night stand, “american dream” becomes a kind of snap-out-of-it condemnation of self pity, and while the immediate topic might be a regrettable night, Murphy broadens it out to shame us for any kind of paralyzing doubt. As he bellows out the words “American dream” (accompanied by a 50s-style “shebang shebang”), we realize that whatever might cause us to feel a crippling sense of powerlessness (like perhaps the state of the country?), that powerlessness is our own fault. Again, a slow dance perhaps not meant for the wedding reception.

A song called “emotional haircut” wears its metaphor right on its face, and in lesser hands, a song about a person getting a haircut in an attempt to change something internal might just sound too cutesy or obvious. “emotional haircut” is neither cutesy nor obvious. The bass guitar-powered rhythm, the feedback-laden guitars, and the sporadic group-chanted lines immediately call to mind the essential late 70s/early 80s post-punk pioneers Gang of Four (see “Damaged Goods,” “Natural’s Not in It,” and “Love Like Anthrax”). “emotional haircut” is a loud, boisterous rock song hiding some complicated and powerful ideas. When Murphy sings “You’ve got numbers on your phone of the dead that you can’t delete,” the guitars tear open your heart a bit.

The final shot of beauty comes with “black screen,” a heartbreaking and poignant rumination on grief. Specifically, Murphy very clearly eulogizes his friend and sometime-collaborator David Bowie, whom he befriended a couple years before Bowie’s death. Murphy makes concrete references to his relationship with Bowie (“You couldn’t make our wedding day / Too sick to travel. / You fell between a friend and a father”). But for those of us who weren’t friends with David Bowie, Murphy makes the eulogy into a broader one, tapping into the “I could have been more of a friend” remorse than many of us might feel after the death of a loved one. And in the closing lines, Murphy explicitly references the Bowie of “Space Oddity” and “Starman” and Blackstar, but also touches our universal need to connect with loved ones after death: “You could be anywhere on the black screen.”

The best art can often reveal the ethereal in the mundane and the universal in the personal. In crafting an album about his particular life in this particular moment, James Murphy has created a masterpiece for all of us in this time.