I can still remember the first time I finished Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried in the 11th grade. For the most part I was a careless learner, but the last story folded me over, like a piece of wire parsing through a slab of clay, leaving just the smooth edges where what you thought you knew used to be. I was young then–complete with fresh teenage pimples dotting my chin and an unruly cowlick that pointed straight upward from the back of my head–but the words from the page came at me in droves. At the time, it was an angry crowd of words, sharp and poignant, elbowing me for space as I tried to make sense of it all. The authenticity and the horror of his language, his truth, so hauntingly naked and unafraid, incinerated the excuse of naivety inside me like one of the villages reduced to ash on the coast of Than Khe.

Some time before that, too, I remember watching the opening scene of Saving Private Ryan. A mere 6th grader at a sleepover, my wet hair still combed and tucked neatly behind my ears by my mother. Some kids my age marveled at the characters in motion and would inch towards the screen as the red dissolved into the slate-colored water in Steven Spielberg’s Normandy Beach. I had a hard time watching then. I have an even harder time watching now.

I can remember now even more vividly, with a certain accuracy that makes the nerves in the back of my neck constrict, a Veterans Day assembly in my first year teaching at Grayslake Central High School in 2012. I remember the principal’s words piercing through the silence of an auditorium filled with aging soldiers–old, tough guys with their bodies calloused–adorned with decorative medals, stars and ribbons. I remember the words he spoke, originating from the 17th parallel to weld them together for life, regardless of war, religion, ethnicity, or infantry regimen. “Hey, man. Same mud…same blood.”

More recently still, even in solace while watching Band of Brothers on a Sunday morning or in a crowded Chicago theater during American Sniper next to my weeping girlfriend, war movies don’t come to me without discomfort. I always feel as though I have just awoke sweating in the center of someone else’s funeral sermon. The thought always crosses my mind, only to then dart around in my stomach, whether it’s almost disingenuous to seek entertainment from the heartache of these stories.

Because how many of us remember Rat Kiley, Captain Miller, or Lewis Nixon?

And perhaps that is what the lasting message of war movies is: people forget.

As much as war literature or film is meant to stir the cool blood in your stomach into motion with the rest of the pool that warms your soul each day, it never can cross that threshold alone. It can never take that last step, the last erudite instruction that reveals to you: this is how it was, this is how it felt, and even now, this is how it is.

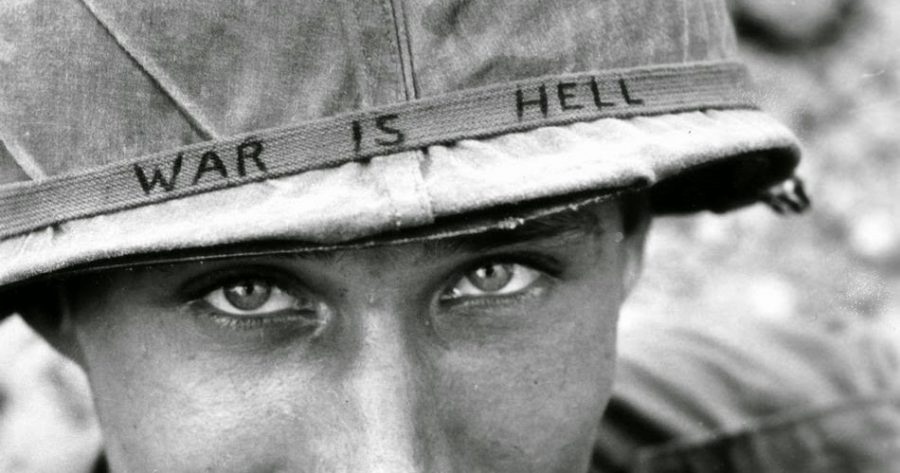

We can never fully understand what it might feel like–the power you might hold, the vulnerability that lay just one small trap or mortar round in front of you. It’s like an amalgam of clips that never blend into setting the picture in motion. It’s still frame, merely two-dimensional.

And with that, we all know Veterans, real live ones–at the VFW or the with the Am Vets hauling away a used couch from your garage–but this Veterans Day, don’t pretend to understand their experience. War is war’s only teacher. Thankfully, many of us will never have to face the shadow of war when it spits on our shoes, for we have been so blessed to stand on the shoulders of strangers. It never mattered to them when the consequences were all too real in Pear Harbor, Korea, Vietnam, Iraq, Afghanistan whether or not we civilians understood the nature of the sacrifice that their lives entailed.

Understanding is not essential. Appreciation is.

It isn’t the popular choice amongst veterans to share the colorful strokes of the sky from their time at war, or the gripping details of both action and idleness in their time of duty. The vast landscapes, although presumably breathtaking in their expanse and power, bear with it–at the risk of sounding cliche–the weight of the world. And that latency, seemingly so long and unperturbed on what seems like the far edge of the world. How can you pretend to transfer the weight of that language to some other human who has never been there? How can you encapsulate all that swims around aimlessly in the brain until it is triggered into decipherable words and attainable paragraphs with seamless entryways into a story’s message?

Perhaps it’s like the words I was left with from Tim O’Brien in 11th grade English some time ago.

“You cannot tell a true war story, sometimes it’s just beyond telling.” Tim O’Brien

So today I ask you to desperately seek out a veteran. Reach out your hand, look them square in the eyes that have seen what you cannot comprehend, and thank them. Thank them for allowing you to never think about what you haven’t had to think about. Until now.