I live and have grown up in a world experiencing a rather remarkable time of world peace. Statistically speaking, never before has so much of the world lived under democratic governments–we’re wealthier, healthier, and better educated than any of our ancestors, and it has been decades since the last major war between world powers. My biggest concerns in life revolve around keeping up my GPA and making sure I get my calculus homework done on time. It’s safe to say I don’t know a world bound by war. I don’t know what it’s like to have my parents, my siblings, myself drafted into a conflict I wanted nothing to do with in the first place.

There are so many things I simply don’t know, questions I’ve wanted to ask but respected the people who actually know the answers to my questions too much to ever voice them. How could you say goodbye to someone knowing there was a very good chance you’d never see them again? To a certain extent, we all live with the fickle nature of our future, but most of us have never knowingly put ourselves in a position where the odds of us coming home in one piece were less than guaranteed. I haven’t known a separation quite so definite, one where that could be the goodbye, the very last time I lay eyes on someone I love. I don’t know anything other than a temporary goodbye, so how do you reconcile the permanence of it?

Where do you find the meaning, the value in this sacrifice you make? Before you even get to whatever may occur during your time spent in service to your country, you first are ceding whatever plans you thought you had for your life in favor of being part of something greater (or so you hope). You suspend your way of life when you go to war–the sheer amount of things you put on hold, experiences you miss out on, or even forfeit altogether. How do you not get caught between two worlds, the before and the after, lost in a sea of regrets and if only’s?

If there is a threshold you must cross, a point of no return in which you offer up your personal hopes and dreams and desires in order to further a higher agenda, where (or when) is it? As a 16-year-old girl fortunate enough to be born during this day and age in one of the best-off places in the world, I struggle defining myself through doing what I love and promoting what I believe as a person. I am not in some foreign country, separated from my family and friends, forced to fire a gun or take a life. I don’t understand how you find yourself in such a situation, find identity and purpose as being one among so many.

How do you not lose your integrity, your humanity? Do you? Is there an experience that irrevocably separates who you were from who you are? I’ve lived enough life to know that even the smallest of experiences have the power to shape you as a person, and that if you let enough of these small experiences pile up, you can look up and not recognize the person staring back in the mirror.

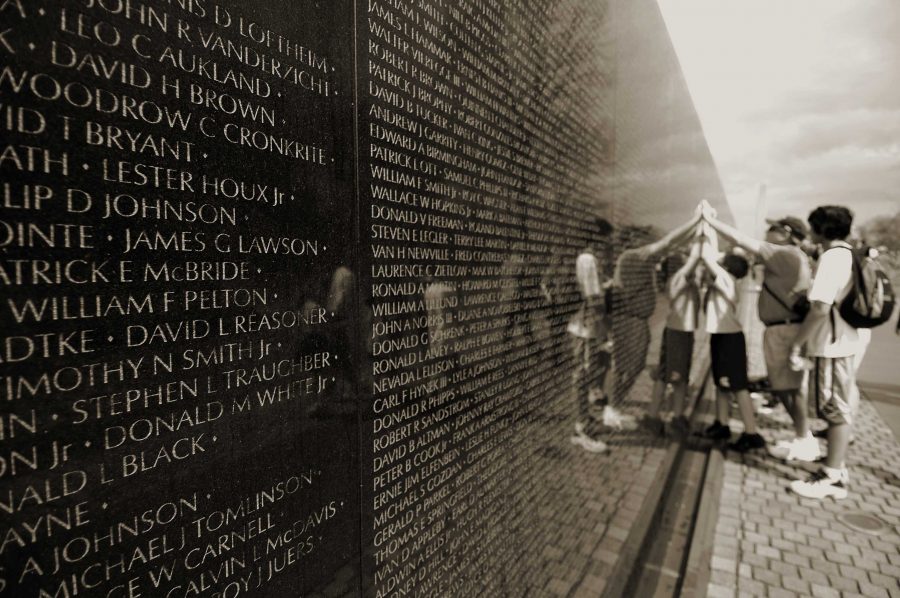

After enough time at war, when you look in the mirror, who do you see? The horrors of war I cannot even begin to fathom, much less comprehend the full extent of. In school we tend to study wars as plot points, climaxes in a narrative, analyzed in terms of cause and effect. We don’t dwell on the details, the people, the measures taken in order for one power to be victorious over another. We see them as a means to an end, never stopping long enough to account for the lives lived before the death count, what it took for the casualties to pile up so high. All the choices you make, the orders you follow, again, the seemingly innocuous means to some brutal and horrifying end–who do they create?

What does it cost to bring yourself to the point of taking a life? Is it even appropriate to ask? I was raised in a Catholic home, taught that only God gets to decide who lives and who dies. I was also taught to love everyone, because everyone’s got a mom, or a brother, or a best friend who loves them and will miss them when they’re gone. There is someone out there who will mourn the life in front of you, the person behind the fatigues and the gun and the “Enemy”–how do you take that away? Does it not go to your head, mess with your sense of right and wrong? Is there a right and wrong in war? Though I don’t know much, I do understand that war tends to resist simplicity. Does it ever really end? Or do the eyes of those not with us anymore follow you long after the treaty’s been signed, and you’ve been shipped home? After such a life-altering event, though you might be home, do you have a home anymore? Or at that point have you seen, done, lost too much, brought light to too many things that should have stayed in the dark?

Can you fit such inhumanity within the confines of the English language, attach meaning and sense to actions that have neither? And at the end of the day, when it’s just you and your thoughts, with those you love asleep in the next room, where does your mind go? How do you justify what you’ve done, or what’s been done to you? Is there a way to put any of this into words?

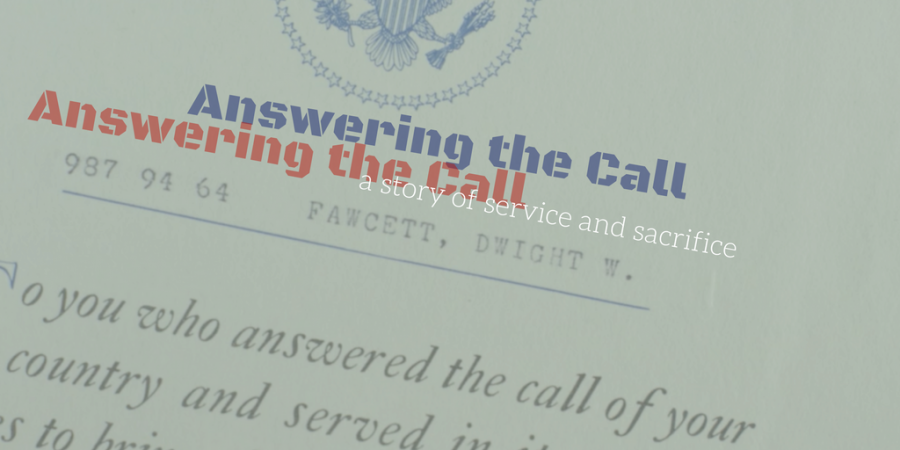

The obvious truth is that I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, and I pray to God I never will. But out there are countless veterans who do, who understand what it means to sacrifice your life for the greater good. I have the life I do because others had the courage to answer when their country called. I am allowed to spend my time preoccupied with school and sports and Snapchat because I’m blessed enough to have such brave men and women out their fighting and defending me, defending our country, our right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And even though I don’t know what it means to take a life, to fight in a war, to be a Veteran, I know that they are the reason I am here today, living the life I do.

Because to me, Veterans Day means never knowing the answers to all of the questions I ask, and for that, I am perpetually and unequivocally grateful.