Fear: The Asian-American Experience

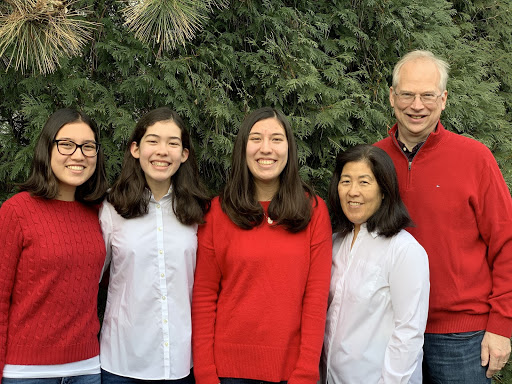

Margot Pierce (far left) and her family. An Atlanta shooting spree has brought attention to a surge in Asian hate crimes,

March 28, 2021

About a month ago, my family was sitting down to dinner when my mom asked, “Do you think I need to be more careful when I’m out? Because of the violence that’s been going on?”

The question initially took me by surprise – these days, my mom barely ventures outside the North Shore, and I’ve always felt pretty safe in the places that we go. The more we talked about it, though, the more worried we all became. Why are we worried? Because my mother is Japanese-American, and we are Asian American.

Anti-Asian hate crimes surged 149% in 2020, despite an overall drop in hate crimes by 7% last year, according to a study done by the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. Examples of such violence have circulated the internet, including this video of a 91-year old man being shoved to the ground while walking down the street in broad daylight. Another man died after a similar incident.

The most shocking hate crime, however, came this month, when a 21-year old man went on a killing spree, murdering eight people at three Atlanta-area spas. Six of the victims were women of Asian descent, dying in a senseless act of racially motivated violence. As a young Asian American woman, hearing this was terrifying.

It was a hate crime.

Not just a shooting.

A hate crime.

The murderer said he has a “sex addiction,” claiming that his actions were meant to eliminate a “temptation.” His claims bring to mind an overwhelming array of historic stereotypes and actions that target Asian Americans. For one, the perception of Asian women as hypersexual and “exotic” dates back to 1875, when the Page Law was put into effect. Meant to prevent the migration of prostitutes to the United States, the law effectively excluded all Chinese women from entering the country. Even from that early on, Chinese women were viewed exclusively as prostitutes, and that perception of Asian women has persisted.

There are many other examples of discrimination against Asian Americans in United States history. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act prevented immigration of Chinese to the country in an attempt to maintain white “racial purity.” Other immigration policies have perpetuated the concept of “yellow peril,” or the idea that East Asian people are a threat to Western society.

The marginalization doesn’t stop there. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor during World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, ordering the evacuation and incarceration of Japanese Americans. My grandfather, Robert Masao Sasaki, was 16 years old at the time. His family was first sent to a fairground to be “processed,” then relocated with his family to a sugar beet farm in Montana. My grandfather and his siblings were American citizens; they knew no country other than the United States, the same country that was now treating them as criminals. They left their family farm in Washington behind, but the Sasakis were lucky. They never saw the inside of the American concentration camps, and they had a family friend that protected their farm while they were forced away from it. Others were not so fortunate. Japanese Americans lost homes, businesses, and livelihoods during those years. They were hated on, called the enemy by their fellow citizens.

Anti-Asian discrimination didn’t disappear with the elimination of those immigration policies or the closure of the internment camps. What the events in Georgia have made painfully clear is that racism against Asian Americans is very much alive.

Almost as disgusting as the crime itself was the seeming rationalization of the violence by Capt. Jay Baker, an officer assigned to the case. In a press conference, Baker claimed: “Yesterday was a really bad day for him, and this is what he did.” I’ve seen some social media comments defending Baker’s statement, claiming that Baker’s comment was taken out of context. I thoroughly disagree. Baker’s comment, in context or out of it, sends the wrong message.

This violence needs to be unequivocally condemned, and mentioning that the shooter had a “bad day” as if that somehow relieves some of the atrocity of his crimes, is unacceptable. Whatever the shooter’s convoluted reasoning, this was a hate crime, and no one should be calling it otherwise. Calls have been made for Baker’s resignation, especially after a Facebook post from March of 2020 surfaced, in which Baker advertised the sale of t-shirts that read “COVID-19, Imported from Chy-na.” In tandem with his statements on Wednesday, it’s clear that Baker is unfit to serve.

It’s hard not to wonder whether the murders would have happened if the former president hadn’t perpetuated anti-Asian rhetoric. On March 16th, 2020, exactly a year before the attacks, former President Donald Trump tweeted the phrase “Chinese virus” for the first time. A week later, #chinesevirus was the dominant term concerning the virus on Twitter, often accompanied by other anti-Asian hashtags. Racism, further emboldened by the former president, has begun to run rampant.

As the pandemic accelerated hate-related incidents, an organization called Stop AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) Hate was founded to track them. 3,795 incidents were reported by the Stop AAPI Hate reporting center from its foundation on March 19, 2020 to Feb. 28, 2021. Over ⅔ of the incidents were reported by women. People in the AAPI community have experienced physical and verbal harassment, been shunned and refused service, and even been blamed for COVID-19. Sound familiar? Even decades after the repeal of anti-Asian legislation, things don’t feel so different for a lot of Asian Americans.

We’re scared. This isn’t an isolated problem. There have been hundreds of hate crimes in the past year, across all 50 states. This is something that cannot and should not be minimized by the media or by politicians.

Don’t call it a shooting.

Call it a hate crime. That’s what it is.

As with the Black Lives Matter protests, Women’s March, and countless other social justice movements, it’s clear that nothing is going to get better for any of us unless we all work together to make it better for all of us. So, support BLM. Be a feminist. Celebrate Pride. Stop AAPI Hate. They all work in tandem.

This week, when my mom brought up the hate crimes, she was no longer asking whether or not she needs to watch her back.

“I need to be more careful, because I’m not really looking out for potential dangers when I’m out.”

She shouldn’t have to. My mom, my 88-year old grandmother, my aunt and uncle and my family, shouldn’t have to look over their shoulder every time they’re out in public. They shouldn’t have to live in fear.

Let’s change that.

Maigler • Apr 2, 2021 at 12:07 pm

Margot, excellent work. This issue is so disturbing and you have helped to put it into context. Thank you for writing it.

Haley Zarek • Apr 2, 2021 at 9:16 am

Such a well-written and powerful article, Margot.

D. Schneider • Mar 30, 2021 at 6:58 pm

Thank you for writing this important perspective.

Chris Landvick • Mar 29, 2021 at 1:31 pm

This was well written Margot. Thank you for speaking your truth.