The End of The World As We Know It: A Home In Ashes

This is an ongoing column called The End of the World As We Know It, where I will attempt to show you what our future will look like if we continue to destroy the environment at our current rate. These stories may seem like worst-case scenarios. They are not. Based on predictions from leading scientists and my own personal experiences, know that, without a significant change, this is our future. Thank you for reading.

March 8, 2019

A young woman stands on the scorch-scarred sidewalk before her childhood home. She can barely see the initials she had etched into the cement under the char and embers. The twin trees between which a tire swing had once hung were ash on the barren lawn; the tire itself, a sad lonely puddle before her home. She gazes across the front lawn. She glances at the run of grass on the side of the house where she and her brothers used to play soccer. Now, only cracked earth, coated in ash, remains.

The woman begins the walk up her driveway, the one that she had made so many times as a child. Past the plots where her mother used to cultivate everything from roses to daisies to tomato plants. They are sown with cinders now. Up to the doormat that used to read “Welcome Home.” The rubber beneath the burnt carpeting has long since melted its way between the bricks of the front porch.

She steps inside, or at least what would have been inside. The roof had crumbled inward long before she arrived, blocking off the rest of the house. The room where her family would play Trouble and Sorry and Monopoly, crushed. The kitchen, where she used to practice the flute for her mom, nothing but rubble now. The stairs up to her childhood bedroom, once bedecked with American Girl Dolls and a small, stuffed rabbit, pulverized. The raging inferno that swept through her hometown had destroyed everything. Everything but the memories. Dreams of taking her own children home to see where she had grown up, gone in an instant. Hopes of measuring their heights against the marks on the wall from when she and her brothers were young, shattered. Any sense of nostalgia, of home, in this now ruined town, burnt up. The woman turns around and slowly trudges out, leaving behind her home in the ashes.

As I am sure you have all heard, this past year was filled with raging infernos that terrorized the denizens of the West Coast, especially California. Just last year, there were approximately 8,527 individual wildfires scorching about 1,893,913 acres of California. These fires cost the state of California, already over $464 billion in debt, $3.5 billion in damages, including $1.7 billion in fire suppression. These brutal fires claimed the lives of 98 civilians and 6 firefighters last year.

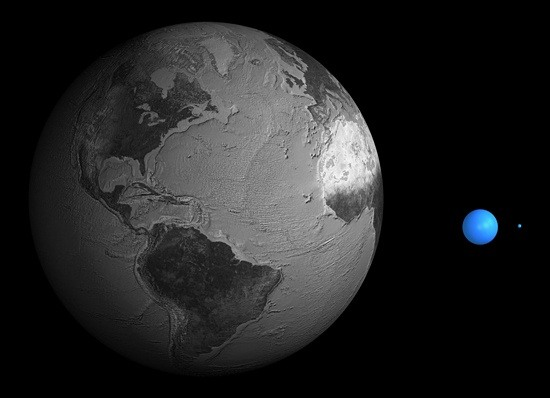

And yet, in spite of these vindictive damages and tragic deaths, we still do not change our ways to prevent these massive wildfires from happening. First of all, in California, climate change has resulted in increasing temperatures and decreasing rainfall and humidity. This dries dead vegetation even more and therefore increases wildfire risk.

People are also continuing to move into space in between big cities and forests, so-called the urban-wildland interface. These areas are extremely inclined to burn, as they exist on the edges of forests, where grasses and small shrubs grow in great abundance. When this vegetation dies, it burns and it burns well. Towns built in these regions are hence far more susceptible to massive infernos that can quickly get out of control.

And finally, the worst mistake of them all, the one that allows these fires to, on occasion, burn across vast swaths of land, is that we have a long history of fire suppression. Much of Southern and Central California is taken up by two primary biomes–the chapparal and the grassland. Both of these biomes are characterized by short grasses and small shrubberies outgrowing all other types of vegetation. The reason these small plants can outlast larger trees? Regular cleansing via wildfire. Traditionally, these flames would course over the region every so often, killing young saplings and larger bushes, but the grasses would survive. The stalks above the ground would burn up, sure, but after a few weeks or so, new stalks would rise. These fires would burn rather regularly, burning up dead vegetation and keeping the ground free for new growth. However, as humans are wont to do, we meddle in the ecosystem and have put out these small, cleansing flames whenever possible. Therefore, the small amounts of dead biomatter that would have been burnt off slowly by regular cleansings have instead piled up. This mass grows and grows and grows until one day, there is a spark. Then, instead of burning just the small dead vegetation from say, the last few weeks or months, huge infernos scorch the countryside, burning years worth of biomass in one endless firestorm. Without us, without our meddling ways, the environment wouldn’t have these blazes, torching California. We wouldn’t have billions of dollars worth of damages. We wouldn’t have over a hundred lives lost. So don’t blame Mother Nature for the embers that were once homes, neighborhoods, and towns. No. We ourselves have turned our own homes into ashes.