Cheat Code

Is it easier than ever to cheat in high school?

At 12:30 A.M., after getting home from practice at 9, talking with your mom till 10, eating at 11 and showering at midnight, it’s time to start homework. Because of pressure from your parents, you’re enrolled in four AP classes, and all four have assignments due tomorrow.

But that Spanish homework and the physics worksheet are also due. Staying up a full hour later doesn’t make you excited, and your phone is sitting right beside you…

By easily texting a friend, you get pictures of both assignments and an hour of sleep is saved.

Congratulations. You have just committed academic dishonesty.

A survey of about 260 LFHS students reveals that about 82 percent of students know someone who has cheated in class, in sports, activities, or otherwise outside of school.

At the beginning of the year, students are asked to sign a paper verifying that they have read and understood the student handbook. Within this handbook is an entire section regarding academics, and within that section, a part about academic dishonesty.

The student handbook makes cheating a significant part of their academic description, providing a lengthy definition and list of consequences. How often do students discuss cheating? How much of it goes unsaid between students and their teachers?

In order to talk about academic honesty, otherwise known as cheating, it is important to note that academic honesty is an umbrella term. Cheating can include copying, “borrowing” information, buying an assignment, plagiarizing, or even flat-out cheating on a test.

You Copy That?

A survey of 260 LFHS students reveals that about 30.5 percent admit that they have copied a friend’s homework once or twice in the month. However, 60 percent of students have not copied homework in the past month, yet 10.4 percent admit to copying once or twice a week.

These numbers reveal that about a third of students admitting to copying homework. “Since I’m doing everything on Google Docs, kids can just share it,” said physics teacher Matthew Wilen. “I’ve caught that, where I’ve looked at a Google Doc and it’s shared with a friend in class.”

Wilen went on to explain that he does not give credit for his homework assignments because of the ease in today’s technology.

“I keep the onus on the students by doing pop quizzes where you can use that homework, so I guess if you copy it, you have something,” Wilen said. “It’s been very evident where students that do homework do statistically much better than the students who don’t.”

Senior Katherine Jemian offered a student perspective on the action of copying. “I think students copy, most frequently, homework that has been completed because [homework] is for completion first of all, and they don’t see the homework [itself] as benefiting them,” she said.

“A benefit of copying someone’s work is to see the method behind it,” Jemian remarked. “Honestly it depends on the kind of student and the load the teacher dishes out.”

The boundary between ethical and unethical has also evolved because of technological advancements. “The thing that has crossed the line is copying and pasting from the internet,” Wilen said. “The technology has gotten so much better to the point where copying and pasting can look nice, where I remember when copying and pasting into my notes, the formatting would be all messed up.”

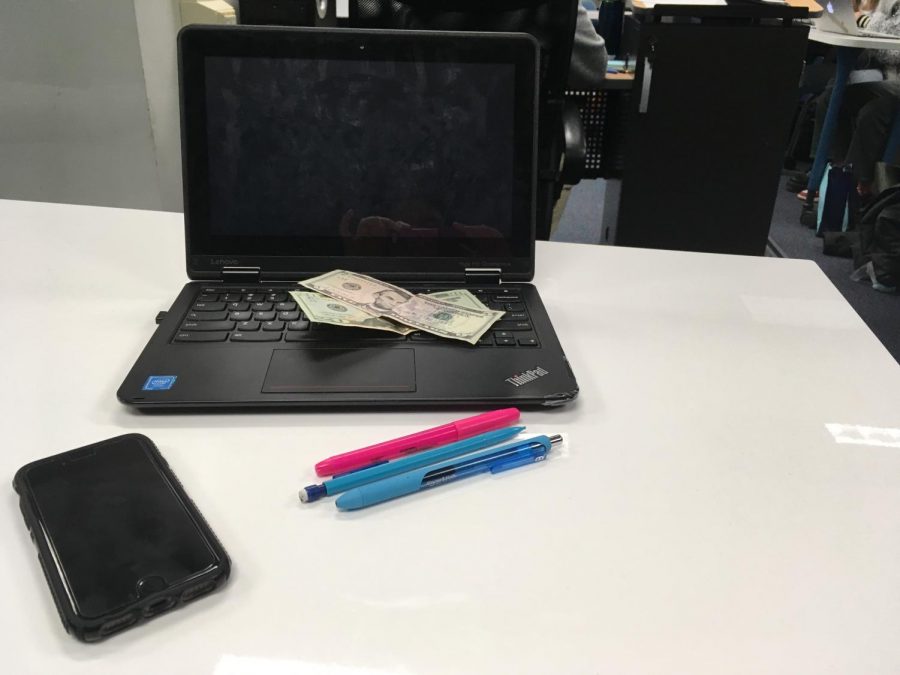

The ease of technology is a benefit to students. “Tech is a big old mediator in academic dishonesty. One text and a whole test can appear,” Jemain said. “For a completion grade, perfect fix.”

Jemian also remarked on the consequences of copying, especially the long term effects. “Long term (unless you already know whats going on) is just like being absent,” she said. “Without that reinforcement, it’s not gonna stick as well as the other stuff.”

Because of resources like Turnitin.com, Wilen believes that although it is easier to cheat, it is also “easier to catch.”

Does cheating surprise Wilen? “Yes and no,” he said. “On the homework, labs, and other assignments it does surprise me how blasé they are, saying ‘Oh I forgot to do this, just send me a text message with a picture of everything.’”

Wilen went on to admit that in high school he would forget to complete assignments, and rush to complete them the period before off of a peer’s work.

“It surprises me how many people are open to that, but at the same time, I’m sure I did it more than I should’ve in high school. It’s a part of life,” he said.

Borrowing Some Words

“I know it doesn’t sound like the student, and you almost don’t want to know that it’s true,” English teacher Jane Eccleston said regarding plagiarism when it comes to her students. “There’s nothing worse than having to put a line from an essay into Google because you just can’t let it go, and when the whole thing pops up, it’s like this sinking feeling.”

While plagiarism is most often associated with writing and essays, the term also refers to information and ideas being taken and used as one’s own.

“If you’re confused by something in English, the instinct is to look it up and figure out what it means,” Eccleston said. “You’re supposed to be confused, it’s supposed to feel ambiguous, you’re supposed to be struggling, you’re not supposed to believe that there’s a right answer out there.”

By using Sparknotes and other online resources, the student not only gets the plot of the story being read, but also is taking interpretations that are not their own and using them as their own. In other words, plagiarism.

“I don’t hear about it from other people, but plagiarizing itself is common I feel,” Jemain said of plagiarism. “A quick copy paste on the same account leaves no tracks.”

Beyond the academic dishonesty portion of plagiarism, something else bothers Eccleston as an English teacher. “For me, it’s like why are you taking the chance to learn away from yourself?” she said. “[Different student interpretations] show you something about the way you see the world.”

For Eccleston, the line between cheating and learning lies in collaboration.

“Healthy discussion and puzzling through something together and being influenced by each other’s ideas when it’s a give and take–that’s the best way to learn,” she said. “It’s not collaboration to go online.”

This sentiment is shared by the students of the aforementioned survey, where about 93 percent of students believe that discussion of ideas is not a form of academic dishonesty.

Plagiarism is not exclusive to the English department, or writing itself.

“Probably the most common thing is where the student is actually plagiarising themself,” Director of Bands Janene Kessler said. “We get that with scale tests, for example, and if a student gets a really good recording one year and they hold onto it because they know we are going to test on those same scales another year.” Kessler now requires students to make video recordings of their scale tests to verify that their playing is original and current.

Kessler also described an incident where a student re-submitted an assignment from the previous year, only changing the title. “He really thought he was going to get away with it,” Kessler said. “He was a good kid, just trying to cut corners.”

Online Test Taking

“This is harder,” Wilen said. “Most of the students that end up in the same place at the same time working on a test are generally not going to do much different whereas if you have someone really struggling with physics sitting down with someone in AP physics.”

Wilen not only has to attempt to monitor activity on the student end of his tests, but he also has extra work to do on his end to prevent academic dishonesty. “I go through all my test questions that I give online and change them,” Wilen said. “Quizlet does have some great resources but I’ve also had students [that fall for a similar answer that has been changed because I researched it beforehand].”

When asked about how much extra work has to be put in on online testing, Wilen explained specifics. “It’s the test banks,” he explained. “I’ve taken them and rewritten every single question–over a hundred questions–because of online resources.”

Paying Your Way

“Last year we had our most interesting case,” Kessler said. “This was a student in our honors program who boasted to me about being paid to do someone else’s Aurelia.”

Aurelia is a software used by honors music students for ear training and music theory exercises, with assignments per quarter. “It took repeated questioning before it dawned on this student that what he had done was wrong,” Kessler said. “I was astounded.”

“He eventually brought it down to two students who had paid him money,” Kessler explained. “It’s an online assignment; there’s no way we would’ve known that it wasn’t that student doing the work. It was really disappointing.”

Why the music department? “The most upsetting thing was the student saying ‘Oh don’t worry I wouldn’t do this in any other class,’” Kessler said. “Clearly he didn’t hold himself to the same standard, maybe because it’s an elective. That was very disturbing for me to hear.”

“You don’t want to make generalizations, but there is definitely an aspect of privilege that we have here,” said Kessler, referring to the affluent community of LFHS. “That’s why we have to be especially careful in how we handle these situations.”

When told about the incident in the music program, the reactions of other teachers ranged from shocked to unfazed. “It does surprise me,” Eccleston said. “Because it seems so extreme. I guess it shouldn’t surprise me–it’s hard to imagine that happening with high school kids.”

“It doesn’t surprise me,” Wilen said. “During grad classes when I would get stuck on something and look it up online, on the side of the site ads would pop up saying ‘Buy this paper,” or ‘Pay someone to write this for you.’ I don’t see it not happening here.”

“I can’t even fathom that,” said Dean Frank Lesniak. “I can’t imagine–even if it was not against the rules, I wouldn’t be paying someone. When I was in high school, I didn’t have the means to pay somebody.” Lesniak said this is somewhat “a temptation that kids have. They have the money, they have access to the money, and they use it for negative things.”

Beyond this isolated incident, paying for assignments does not seem realistic from a student perspective. “Paying people might happen, but I think that’s saved for the movies,” Jemian said. “I feel like I would confide in a friend to write my stuff and wouldn’t accept payment, but that’s just me.”

A Learning Process

While being caught can very well be a serious incident, Lesniak pointed out how the treatment of cheating at LFHS is not all it might seem to be.

“The message that we send to kids all the time when there is academic dishonesty is what’s your plan after high school?” he said. “Most student say ‘I’m gonna go to college,’ right? If you [cheat] in college, they just boot you outta there, you’re done.”

Lesniak emphasized that colleges have a “zero tolerance” policy towards cheating, “even if it’s an accident.” “Even if you’re not truly meaning to plagiarize, but you’re using too many of someone else’s words and not giving them credit, colleges will just say ‘you’re done.’”

“Kids are kids, and they do dumb things sometimes, and that’s our job to be there to correct them and help them realize the error in their ways,” Lesniak said, “When you go to college, you’re an adult, you’re in the real world. That’s our education for them–there’s no tolerance for that.” Guiding students to make honest decisions while in high school and focusing on the big picture have an impact on how academic dishonesty is treated in this environment.

Going The Extra Mile Thanks To Technology

“It’s a whole other thing to think about than when I first started,” Eccleston said of cheating through technology. “It was not as prevalent. I definitely don’t think [cheating] happened as much. I’ve become used to having that in the back of my mind.”

Eccleston calls the role of technology in cheating “the biggest single factor. It just makes it so easy.”

Students agree–according to the survey, 76 percent of students believe that technology makes cheating easier.

“You have everything at your fingertips,” Lesniak said. “When I was in school, I didn’t know that I could type into Google ‘give me an essay’ and *snaps* there it is. That is available to kids 24/7 right now.”

Are The Hard Classes Too Hard?

“I never had tons of homework; I had homework, but nothing like ‘I’m not sleeping tonight.’ That never happened to me,” Lesniak said. There was a consensus among some teachers that the rigor of some classes may provoke students to cut corners in order to do well in the myriad of classes that they are taking.

“People might be cheating here for different reasons than they might be in other schools,” said Kessler. “The pressure here to maintain high grades and to take classes that are challenging is probably greater than in some other schools. You might have cheating for different reasons.”

“You hear of kids doing two, three, four hours of homework a night,” Lesniak said. “It’s different; it leads to some kids rising to the occasion and it leads to other kids trying to rise to the occasion, falling short and saying ‘I need something else,’ and then they cheat.”

“I feel that the way you’re raised has a lot to deal with underlying morals that unconsciously drive one to cheat, but that’s a select percent of the population here,” Jemian said regarding cheating in the student population.

Throughout time, academic dishonesty has evolved because of advances in technology and even advances in class difficulty. By looking past the definition provided by the student handbook, it is evident that academic honesty is an umbrella term–it stretches far beyond the two words that it appears to be.

“I have to know that I’m kind of just saying it,” Eccleston said in regard to warning her students against cheating. “It’s probably gonna happen anyway.” When mentioned that some teachers don’t even mention cheating, Eccleston commented “Is that like tacet approval of doing it?”